There’s a Reason It’s Hard to Say No

My love interest at the time was completely wrong (and kind of a jerk). Saying no is difficult, especially for those of us who aren’t cisgender men. After all, we’re trained from birth to be pleasing and agreeable in our intimate and professional interactions, and to prioritize others’ emotions at the expense of our own. This expectation permeates our work and home lives. Around the world, women do two to ten times the amount of unpaid domestic, emotional, and care work as men—anything from taking care of children to cooking dinner to checking on our partner’s aging mom. Many women are taught that it’s more important to please our partners than ourselves. Women are also the bulk of people in service jobs, like restaurant and sex work, which depend on prioritizing others’ needs. Workers in these professions frequently face financial loss, and even sexual violence, when saying no to unwanted sexual attention, part of the reason tipped workers experience some of the highest rates of sexual harassment of any field.It takes a lot of courage to open ourselves up sexually. It’s kind to acknowledge that vulnerability when we reject someone.In our intimate lives, saying no isn’t just uncomfortable: It can be downright dangerous. In sexual situations where we feel unsafe, saying yes to some kinds of sex can be a strategy to avoid more extreme violence. The same goes for abusive relationships, where we may defer in an attempt to protect ourselves from further abuse. Even when saying no isn’t dangerous, the pressure to be liked or to not hurt others’ feelings often causes us to agree to things we don’t actually want. In the anecdote above, for example, I wasn’t physically scared of my neighbor, but I was anxious about coming across as hostile if I avoided his too-forward small talk. Similarly, I didn’t think my love interest would harm me, but I did worry he would find me unpleasant or “difficult,” and thus want to see me less.

You Don’t Need a Justification

Here’s the thing, though: We always have the right to say no to sexual attention, without justification, without an apology, and without shame. That’s because affirmative consent, in its deepest sense, isn’t begrudging or coerced. It’s not agreeing to sex just to avoid hurting someone’s feelings, or to convince them to like us. It is, at heart, a full and equal opening of ourselves to another person and experience. If It's not freely given, it’s not consent. It’s natural to want to be empathetic in how we turn people down. It takes a lot of courage to ask someone out or to open ourselves up sexually. It’s kind to acknowledge that vulnerability when we reject someone. If we’re close to someone, or want to continue having a sexual or relationship with them in the future, we may even explain our decision. But at the end of the day, your job is to keep yourself safe—not to manage other people’s expectations. If you’ve rejected someone with empathy, you’ve gone above and beyond, and the moment that person’s sexual attention makes you uncomfortable, or they try to argue or guilt you into saying yes, that’s your signal to make a quick exit. Other people’s feelings about your “no” are their baggage to deal with, not yours.Learn to Listen To Yourself

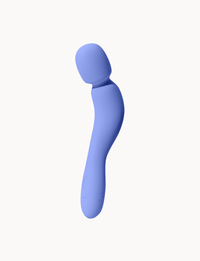

Knowing what we want—and what we don’t want—is easier said than done. If we have histories of intimate trauma, our “no” can be even harder to access. That’s because tactics of abuse and control are especially geared toward alienating ourselves from our inner voice. Gaslighting—or the manipulation of our reality by an abuser—can leave us struggling to trust our own thoughts and perceptions in the long term. To cope, we might avoid feeling our feelings altogether, or dissociate by “zoning out” from reality. These coping mechanisms are understandable and normal, but they also keep us from embracing our desires.Try talking with partners about your boundaries before sex, so that it’s easier to say "no" in the heat of the moment.The good news is that our intuitions never abandon us, even if we’re taught to ignore them, and we can always learn to tune into powerful gut feelings. This begins with the simple act of noticing your body. Check in throughout the day: Are you hungry, horny, tired, cheerful? Do you need to eat, drink, sleep, masturbate? Use this information to practice leaning into your desires by giving your body what it needs. We can bring the same warm, curious energy into our sex lives. Put love and care into masturbation: solo, with a toy, or even with a partner. Approach your body with a sense of gentle, open exploration. What feels amazing? What tickles? What makes you want to cry? Explore new kinds of porn. Sit down with a “Yes, No, Maybe” list and check in with what you love, what you’re not into, and what you’re curious about.