Alexandra Fine, Credentialed Sexologist, M. Psych | Written by Dame

Those who only know slang terms for genitalia may be stumped if “the vulva” comes up in discussion – or in bed.

Quite honestly, that lack of anatomical knowledge is not uncommon and it’s not surprising.

A survey of research on terminology for “male and female genitalia” (sic) sheds some light on the subject. The author examined early childhood messaging which substitutes pet names or slang for the parts of the genitals; he found it can contribute to embarrassment, lack of body understanding and a rigid heteronormative view of sexuality later in life.

So it’s natural that many people don’t actually know, or that they misunderstand, what the vulva is.

Here’s what the vulva is not:

- It’s not the vagina.

- It’s not the entire genital region, or “everything between the legs.”

- It’s not “the sex organs” on those who have vulvas.

- It’s not the “female reproductive system.”

So what is the vulva? It’s the name for all of the external parts of the reproductive system which develop on people without Y chromosomes. More simply, it’s the genitalia on the outside of those people’s bodies. And it’s responsible for much of a vulva owner’s sexual pleasure.

Vulvas all look a little different. But even though the shapes, colors, sizes and placement of external genitalia may vary, the anatomy of the vulva is almost always the same.

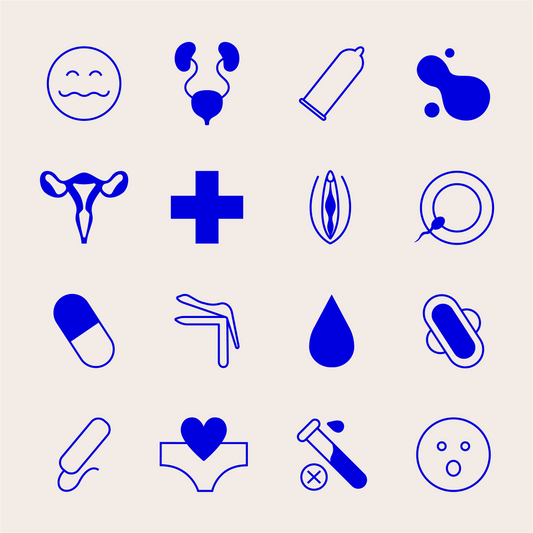

Vulval Anatomy

The Vaginal Opening

Many people think that vulva is just another word for vagina. It’s not. The misconception is probably widespread because society focuses so much attention on the vagina.

Located toward the bottom of the vulva, the vaginal opening (or introitus) might be described as “traffic central.” Babies, and blood from the menstrual cycle, come out of it. Fingers, penises and sex toys, as well as tampons and birth control devices, may all go into it. Needless to say, the vagina itself is quite stretchy, and it terminates at the cervix.

There are two sets of vestibular glands in the region. They’re responsible for keeping the vaginal canal and the vagina itself lubricated (and not just during sexual activity, either). One set is known as the greater vestibular glands or Bartholin’s glands; they’re located on either side of the vaginal opening and their ducts open into the vestibule (described shortly). The lesser vestibular glands, also called Skene’s glands, are at the rear of the vagina.

The mucous membrane known as the hymen, contrary to myth, isn’t a solid piece of tissue over the vaginal opening. And it isn’t always “broken” at the time of first vaginal penetration or sexual intercourse. Some vulva owners are born without one, in others it’s only a small fringe, and even if it’s fully-intact tissue you normally wouldn’t even notice it. Often, the hymen breaks or tears long before any sexual activity takes place. In other words, a hymen isn’t a “sign” of anything, and its presence or absence is nothing to be concerned about.

The Urethral Opening and Vestibule

The opening of the urethra (in anatomical terms, the urethral meatus) is above the vaginal opening. It has just one purpose, but needless to say, it’s an important one: it releases urine carried through the urethra from the bladder.

Both the urethral and vaginal openings are surrounded by the vestibule of the vulva, which has its outer edges at the labia minora (we’ll get to the labia momentarily). The ducts of the greater vestibular glands also open into the vestibule, providing some of the lubrication that is released into the vulva during sex play. The lesser vestibular glands provide lubrication for the urethral opening.

The Labia and the Clitoris

The two concentric, oval-shaped folds of skin which surround the vulva are known as the labia majora and labia minora, but are commonly referred to as the outer lips and the inner lips. Their primary role is to protect the vaginal and urethral openings, but they also release lubrication during sexual arousal. Pubic hair often grows on the outer lips.

Where the tops of the inner skin folds converge there’s a flap called the prepuce, or clitoral hood. Its function is to protect the external part of the clitoris (yes, there are internal parts as well) from friction during everyday life. During sexual stimulation the hood pulls back or can easily be moved aside. It may also be quite sensitive.

That brings us to the clitoris – or more accurately, the glans clitoris. In reality, there are 18 parts of the clitoris and most of them are under the skin; the glans is the only one which is accessible externally. Gynecologists, women’s health care providers and those who’ve read this article are among the select few who know that the “pleasure button” near the top of the vulva is only one component of the clitoris.

It’s quite a component, though. With more than 8,000 nerve endings, the glans is usually the most sensitive part of the vulva. That’s why it’s the spot that often attracts the most attention during masturbation or sex play. In fact, more than a third of those participating in surveys regularly say they’re only able to achieve clitoral orgasm, and another third say that clitoral stimulation greatly improves their climaxes during vaginal sex.

The parts of the clitoris that you’re unable to see, however, play a major role as well. The organ has about the same overall length of a penis, it’s shaped much like a wishbone, and its connective tissue extends all the way back to the pubic bone, in the shape of a wishbone. The most important parts for our discussion are the corpora cavernosa, capped by vestibular bulbs and then attached to crura, or legs. Each play a huge role in pleasure and orgasm, because like the glans clitoris, they’re made from expandable, erectile tissue. Many anatomists consider them to be part of the vulva, even though not part of the external genitalia.

Those parts of the clitoris release lubrication, and fill with blood and swell during arousal so they make contact not only with the glans but with the vaginal walls – enhancing sexual satisfaction. In fact, some believe that a G-spot orgasm is really a clitoral one, produced when the internal parts of the clitoris contact the back of the vagina.

The Cliff Notes version: the glans is the only part of the clitoris that is physically visible in the vulva, but there’s an awful lot going on behind the scenes.

Other Areas of the Vulva

Several other regions are generally considered to be parts of the vulva.

- Mons Pubis: located at the top of the vulva, this is the mound of fat covered by the skin of the vulva, best known for growing public hair. One of the other functions of the mons pubis is to provide a cushion during sexual activity.

- Fourchette and Perineum: these areas are where the inner lips meet at the bottom of the vulva (fourchette) and the region that extends from the bottom of the vulva to the anus (the perineal area). The anus is not considered part of the vulva, and some anatomists do not consider the perineum to be part of it, either.

Potential Vulvar Health Issues

We’ve mentioned that the appearance of the vulva varies from person to person. Differences should be appreciated and celebrated, rather than judged.

However, major changes in the vulva’s condition or appearance may indicate a serious health problem. Among the ones to watch for:

- Yeast infections: 75% of vulva owners contract a yeast infection, often called thrush or Candida infection, at some point in their lives. Itching, swelling, redness, vaginal discharge and pain are the telltale symptoms. It will almost always respond quickly to over-the-counter creams or prescription medications.

- Herpes: Small lesions or ulcers on the vulva, which look like pimples or blisters, are usually a sign of herpes. The virus cannot be cured, but can be controlled with anti-viral medications.

- Other sexually transmitted infections or diseases: Many STDs manifest with swelling or redness in the vulva, or vaginal discharge with distinctive colors or odors. The most common are human papillomaviruses (HPVs), which cause genital warts. The warts may be able to be removed, and the HPV vaccine (administered at early ages) can prevent many forms of the viruses, but there is no cure for the infections.

- Pelvic floor dysfunction: Pain and discomfort in the vulva, accompanied by other symptoms like muscle spasms, difficulty urinating, or constipation, may indicate problems with the ligaments and muscles that support pelvic organs. A doctor should be consulted as soon as possible.

- Vulvar cancer: Although the disease is rare, major changes in the vulva may indicate vulvar cancer, particularly in older patients. Continual itching, pain, thickening skin that changes color, bumps and unusual bleeding are all signs that a gynecologist should be consulted.