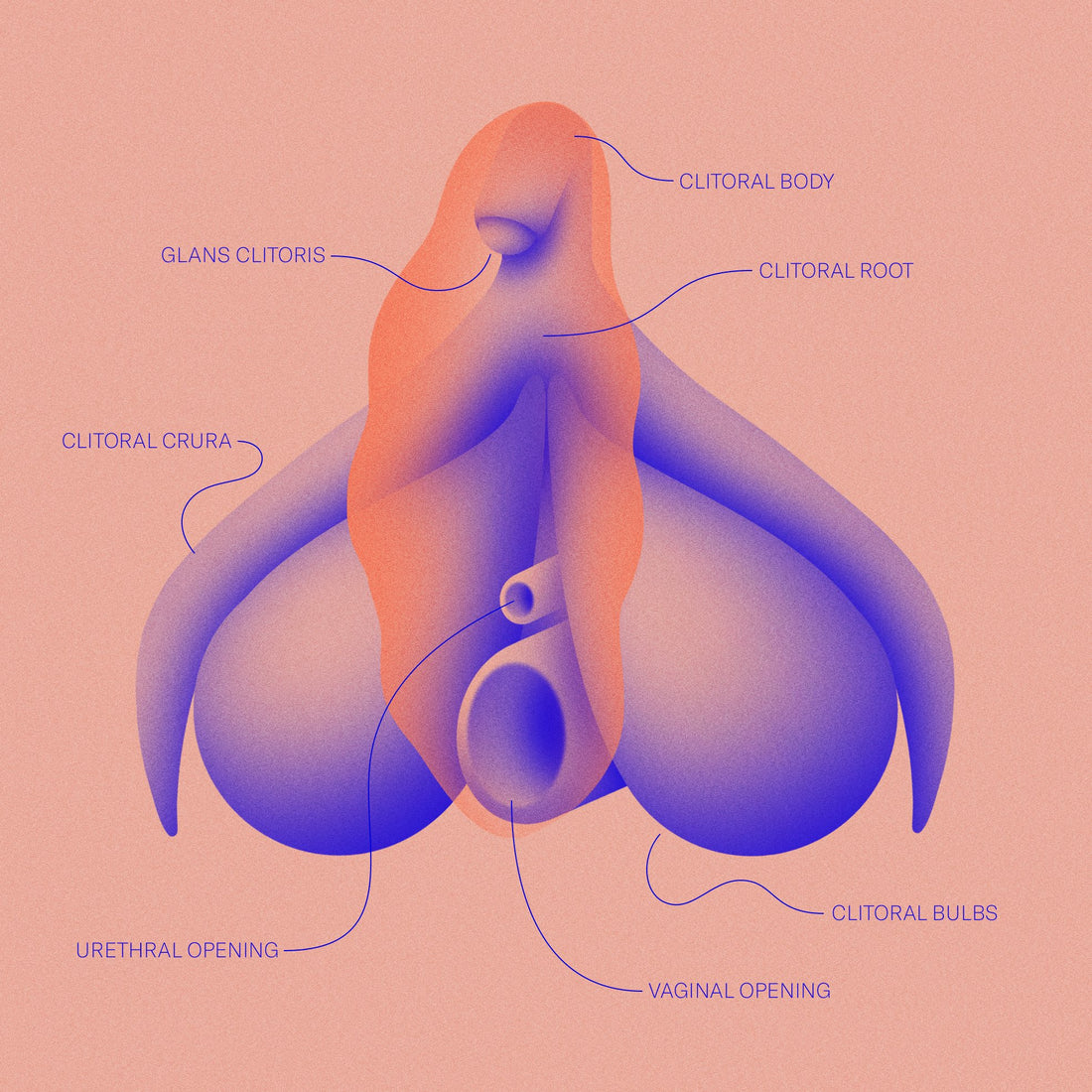

Illustration by Léa Zhang

by Suzannah Weiss

Few objects have taken on as many cultural meanings throughout history as the vibrator. From symbols of women’s liberation to signs of societal disintegration, people love to project their hopes and fears onto these iconic sex toys, even as they are loath to talk about them.

There’s a perception in popular culture that the electric vibrator was invented to treat “hysteria” in women, but this is only partially true. It was actually invented by British physician Joseph Mortimer Granville in the 1880s to treat a variety of ailments in both women and men, says Lynn Comella, Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas and author of Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy Stores Changed the Business of Pleasure.

“Vibrators were initially marketed as a medical technology and home health and beauty devices,” Comella explains. The user manual for one vibrator by the Shelton Electric Company lists asthma, dandruff, impotency, obesity, watery eyes, and wrinkles among the conditions it could treat. The illustrations include a man holding it up to his bicep and a woman buzzing it just above her breasts, her slip’s strap falling to the side. There were also some machines one might consider vibrator precursors earlier in the 1800s, such as 1869’s manipulator, a large contraption with a steam engine attached to a dildo. Another type of steam-powered vibrator had a wooden handle, a crank at the bottom, and a flywheel on top that would make rubber attachments vibrate, says Hallie Liberman, author of Buzz: The Stimulating History of the Sex Toy.

“Vibrators were initially marketed as a medical technology and home health and beauty devices,” Comella explains. The user manual for one vibrator by the Shelton Electric Company lists asthma, dandruff, impotency, obesity, watery eyes, and wrinkles among the conditions it could treat. The illustrations include a man holding it up to his bicep and a woman buzzing it just above her breasts, her slip’s strap falling to the side. There were also some machines one might consider vibrator precursors earlier in the 1800s, such as 1869’s manipulator, a large contraption with a steam engine attached to a dildo. Another type of steam-powered vibrator had a wooden handle, a crank at the bottom, and a flywheel on top that would make rubber attachments vibrate, says Hallie Liberman, author of Buzz: The Stimulating History of the Sex Toy.

“Although its erotic uses were known,” says Comella, advertisers were “coy, using coded language to both hint at and mask the vibrator’s sexual uses.” These toys also weren’t exactly designed for the bedroom. They were as big as drills or hairdryers and as heavy as you’d expect given their size, says Good Vibrations’ staff sexologist Carol Queen. They looked “quite steampunk,” she says, with a motor in a spherical or cylindrical case, a handle made out of (usually painted) wood, and a nose holding vibrating attachments called vibratodes, which came in every shape from cup-like to phallic, depending on the health condition it was designed to treat. Some even had rubber teeth that were meant to move through your hair like a comb, says Lieberman. Others had rectal attachments meant for prostate health or vaginal ones advertised as a treatment for uterine disease.

Vibrators were “a supposed panacea that would cure all ails and also make you feel good: kind of like the alcohol- and cocaine-filled patent medicines that were popular at the time,” says Lieberman. However, doctors eventually determined that vibrators didn’t work, and they lost popularity as medical devices by the ‘30s or ‘40s. Vibrators were marketing for beauty in the ‘40s and ‘50s under the claim that using it on your face or scalp enhanced blood flow to provide a glow or prevent dandruff, but that trend was short-lived as well.

Vibrators were “a supposed panacea that would cure all ails and also make you feel good: kind of like the alcohol- and cocaine-filled patent medicines that were popular at the time,” says Lieberman. However, doctors eventually determined that vibrators didn’t work, and they lost popularity as medical devices by the ‘30s or ‘40s. Vibrators were marketing for beauty in the ‘40s and ‘50s under the claim that using it on your face or scalp enhanced blood flow to provide a glow or prevent dandruff, but that trend was short-lived as well.

Other early vibrators were battery-powered, but these were about the size of a car battery and hence not very portable, says Queen. Nevertheless, porn had begun to include vibrators by the late 1910s, and in the ‘30s, doctors reported their patients masturbating with them, says Lieberman (though she believes people were likely doing so before that). The first phallic vibrators (as opposed to just phallic attachments) arose in the ‘50s, thanks to smaller batteries. By the following decade, the vibrator was being marketed as a sex toy in sex shops and magazines, says Queen.

The vibrators sold in the ‘60s and ‘70s were mostly either penis-shaped or in the form of cock rings, says Lieberman, reflecting a cultural view of women’s pleasure as dependent on penises. The first non-phallic vibrators popped up in the ‘70s, thanks to Doc Johnson, which offered a bullet vibrator, one shaped like a finger, and one shaped like a lightbulb with spikes, Lieberman adds. The ‘70s also saw the invention of the famous Hitachi Magic Wand and vibrating, vagina-like sex sleeves that were precursors to toys like the Fleshlight.

In the ‘80s, the most popular vibrator design was the “smoothie,” which was kind of phallic but without the head. Non-phallic vibrators reached the mainstream in the ‘90s, with the invention of Doc Johnson’s Pocket Rocket, and exploded in the 2000s, with fun shapes like rubber duckies and pebbles, Lieberman explains. “But still, phallic vibrators seemed to be the norm until very recently, probably the past 10 years.”

The shift to less penis-like vibrators is largely due to their appearance on the shelves of drug stores like CVS and Walgreens in the early 2000s, says Lieberman. Since phallic toys may have appeared too obscene for everyday settings, stores were more likely to display bullets and vibrating cock rings.

As designs changed, cultural views of the vibrator changed as well. In the ‘70s, it became a symbol of women’s sexual liberation, thanks to sex educators like Betty Dodson and feminist sex shop owners like Joani Blank and Dell Williams. While sex shops used to be known as seedy establishments mainly for men, these pioneers made women target customers of sex shops and sex toys, Comella explains. “Vibrators were tied into women’s liberation and bringing yourself to orgasm without a man,” says Lieberman.

As designs changed, cultural views of the vibrator changed as well. In the ‘70s, it became a symbol of women’s sexual liberation, thanks to sex educators like Betty Dodson and feminist sex shop owners like Joani Blank and Dell Williams. While sex shops used to be known as seedy establishments mainly for men, these pioneers made women target customers of sex shops and sex toys, Comella explains. “Vibrators were tied into women’s liberation and bringing yourself to orgasm without a man,” says Lieberman.

The vibrator also made several media appearances that helped destigmatize it, such as the 1998 Sex and the City episode where Miranda convinces Charlotte to buy a rabbit vibrator. (The show also spread some less celebratory messages about vibrators, such as that purchasing one could make you cancel your social plans and turn you into an anti-social hermit like Charlotte.) Since then, shows like Broad City have depicted vibrators as more unequivocally positive.

But the biggest change to vibrators over the past century is perhaps that society became open enough about female pleasure to understand that sexual stimulation is one of their (major) uses. Yet in a way, we’re also returning to marketing them for their health benefits, Comella points out. The website for the smart vibrator Lioness reads, “Sexual wellness is a basic human need.” Maude, which sells various sex products, says it promotes “sexual wellness for all people.” And Dame has spoken out for our right to advertise itself in public spaces on the grounds that our products are important for sexual well-being.

The most significant physical changes to vibrators are that they no longer plug into walls and come in a wider range of sizes, colors, and shapes, says Queen. Most are also lighter and easier to grasp or control, and since their creators are more conscious of the materials they’re using, sex toys are more body-safe, says Comella.

Innovators have also been creating vibrators with unique features, such as those that connect to apps for remote partner play. Some, like Lioness, can even record your body’s sexual responses, and others like Crescendo and Dame’s Pom let you customize the toy’s shape, speed, and vibration patterns. There are also some vibrators like Enby that are marketed in gender-neutral ways. Vibrators doubling as jewelry, like the Crave Vesper, let people show off their sex toys. The Womanizer and Satisfyer pioneered the suction-cup design known for inducing orgasms at a moment’s notice. Toys like the LELO ORA 2 are designed to emulate oral sex. And “luxury” vibrators like those listed on Goop have become symbols of wealth.

Many companies have been working on vibrators like Dame’s Eva II that are meant to be worn during intercourse, and Queen believes one future focus of manufacturers will be on perfecting these designs. Other future directions for vibrators will include increased security for app-connected toys, higher battery life, and potentially new materials, she adds.

Given the rise of female-led sex toy startups, we can likely look forward to more vibrator innovations over the next few years. “If the growth of the women in sex tech movement is any indication,” says Comella, “we can expect to see more female engineers and designers entering the sex-toy industry and pushing the envelope of innovation in new and exciting directions.”

-

Suzannah Weiss is a freelance writer focused on gender and sexuality whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, New York Magazine, and more. You can find her on Twitter at @suzannahweiss or on Instagram at @weisssuzannah, or visit her website at www.suzannahweiss.com.